How it feels to be a loving but emotionally incompetent man

I’m one of the lucky ones. A ridiculously unlikely series of fateful chances led me to a loving partner on the other side of the world. We have been happily married for 45 years.

As a therapist, I see the usual outcome of childhood trauma: broken relationships and lifelong emotional difficulties. The stories shared in a recent documentary about the emotional impact of English boarding schools, ‘Boarding on Insanity’, reminded me of my own experiences and prompted me to share my learning.

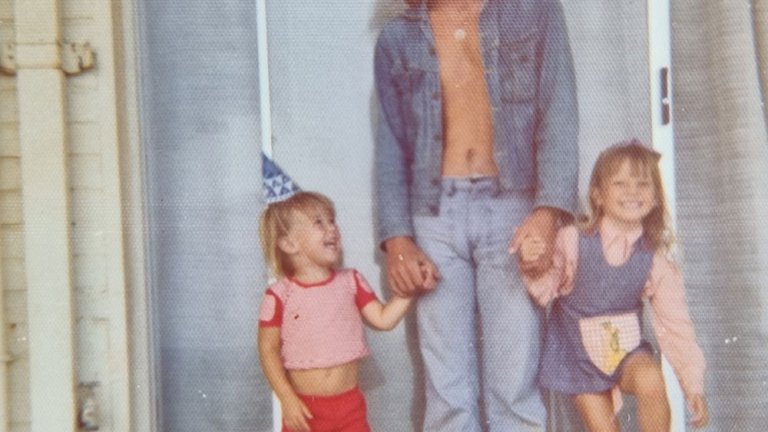

My father was in the British Army so my childhood was fractured across many countries and there was never a place to truly call home. I was a very shy, unconfident and physically timid boy. By the age of ten, my education was far behind that of my peers so my parents made a huge sacrifice to send me to boarding school in England when they were posted overseas. For the rest of my childhood, I was separated from my family three-quarters of the year.

At boarding school, I was friendless, utterly alone in my suffering, and horribly bullied and abused. The one person who was kind to me was the school teacher who groomed me and sexually abused me. Of the bullying and abuse, I never said a word to my parents because it was a shameful secret. They died in their 90s without ever knowing.

As a result of my childhood trauma, I carried three deep wounds into my adult life: disconnection from my feelings (dissociation), a terrifying fear of abandonment, and a dread of humiliation.

I also came equipped with deep insight into the nature of bullies and cruel institutions. This knowledge has motivated my lifetime of efforts to make healthcare more humane and compassionate and to explore the meaning and practice of healing.

For many decades of adult life, I did not believe that the childhood sexual abuse did me any harm. I was also profoundly disconnected from my own feelings and I compensated with intellectual pursuits and a variety of heroic roles. I became a medical specialist in anaesthesia and intensive care doing hi-tech medicine in leading hospitals. Clinical detachment and objectivity were upheld as an important medical attribute. Doctors were never allowed to have an emotional connection to a patient or to display their own feelings; both were deemed unprofessional.

Later in life, when I came across the term ‘alexithymia’ in the trauma literature, it was a revelation. The literal meaning of this word is having ‘no language for feelings’ and it describes profound difficulty in recognising, expressing and naming feelings. That’s me! was my stunned reaction.

My wife Meredith is one of the most loving, kind and loyal people that I know. I have been utterly devoted to her since we married in 1980 but I wasn’t always the best husband. Meredith also has her own experience of trauma but by some miracle, we came together in a way that was mutually supportive, rather than tearing each other apart.

As a result of the disconnection from my own feelings, I was sometimes hugely insensitive to Meredith’s needs or feelings. I could become patronising, intellectual and superior without even being aware of my attitude. At all times, my motivation was to support Meredith, to be a loving husband, and to put things right if I upset her.

One day I might accidentally do something, or be neglectful, in a way that causes distress to Meredith. When she shared her hurt feelings I would feel appalled. Meredith is eloquent in expressing her feelings and her understanding of a situation. From her explanation, I would be able to see it from her perspective and I felt distressed that I had blundered into a situation that hurt her. That incompetence was itself a source of humiliation.

Humiliation arises when we are exposed or criticised, in front of others, as being bad, wrong or incompetent, even if we are innocent and the accusation is unfounded. As a trauma therapist, I am constantly surprised by the extent of fear and inhibitions suffered by highly competent adults as a result of even a single instance of childhood humiliation, typically delivered by a cruel teacher in front of a classroom of students. This shows up in a crushing sensitivity to feedback from a boss, or severe procrastination when trying to start a new assignment. Sadly, my medical training was often delivered by bullies who frequently used humiliation, which was believed to motivate devotion to long hours of study. Ironically, the stress of humiliation inhibits the higher cognitive and learning centres in the brain so the strategy is counter-productive.

Faced with an upset wife, I experienced a nightmare of emotional incompetence. Meredith would implore me, “For God’s sake Robin, just talk to me!”

I often felt that my every attempt to speak and to put things right, just made matters worse. I was lacking in the emotional sensitivity to meet Meredith’s needs and I struggled to identify or name my own feelings. Most of my inept responses seemed to make her more frustrated or angry. I felt profound humiliation at the crass incompetence of my responses, re-triggering childhood experiences of traumatising humiliation.

I felt like I was traversing an emotional minefield, completely blind to when the next incident might erupt. I would go into the traumatic freeze mode, my mind completely blank, and often I was unable to speak at all except to beg forgiveness. My mute response further frustrated Meredith, who experienced me as cold and judgmental.

I want to make clear that these were mostly minor upsets, not anything that threatened our relationship. It was very rare for either of us to get seriously angry, we were devoted to each other and we never tried to hurt or wound the other. Both of us wanted rapid resolution of any upset.

But there was another layer of trauma that also shaped my reactions. As a result of being left at boarding school at an early age, I developed a profound fear of abandonment, which I carried for more than fifty years. If I had the slightest upset with Meredith, I would be terrified that she would leave me, a rationally ridiculous thought given her devout love and loyalty, but nonetheless experienced as a crippling fear. In those moments, I would become like a ten-year-old boy again, too frightened to speak.

This triad of traumas - emotional incompetence, profound humiliation and fear of abandonment - impaired my relationships for decades. I had very few friends, was a loner, was socially insecure and in social gatherings I over-compensated by boasting about heroic adventures or medical dramas. Yet in my professional role as a doctor, I was very confident and also kind to my patients because I empathised with their suffering caused by the inhumanity of medical care.

The extent of my dissociation and emotional incompetence meant that I had little understanding or awareness of what was going on inside me. I didn’t know about dissociation, or understand the traumatic origins of my humiliation, or know why I became so fearful when I felt that my primary love relationship was threatened. These are all recent understandings as I have gradually become more emotionally aware, healed my childhood wounds, and gained experience in a new career as a trauma therapist (I quit my medical practice).

What was that path of healing?

The early years of my medical career were highly traumatising but at least I returned after work to a loving wife and secure home. In my recent book, ‘The Science of Miracles’ I tell the story of weeping uncontrollably after a nightmare duty shift, of three days and two nights, when six of my patients died. I had been a doctor for only one week. Meredith held me while I sobbed wordlessly, grateful that I could at least express my feelings that way.

Alexithymia seemed to play both ways; while I could not name or express my feelings, so also the spoken word offered me little comfort. If I was distressed I needed to be hugged and held. For Meredith, words seemed more important so one of the challenges of our early marriage was learning to use the love language of the other.

Over the decades, the emotional security of our marriage allowed me to drop my defences, connect more with my feelings, and become more emotionally literate. Meredith gently coached me in ways of being more attuned and emotionally sensitive. I learned the things that caused her upset and became more skilled at meeting her needs.

My work on compassionate healthcare led me to explore different philosophies, to practice mindfulness meditation, to begin to let go of self-judgment, and eventually to facilitate many workshops on compassionate presence, human connection and healing. My international campaign for compassionate healthcare resonated with many and, for the first time, I felt the connections of friendship and love from many people around the world.

I discovered the therapy called ‘Internal Family Systems (IFS)’ and gained insight into the nature of my inner wounded child and the protector roles we create to shield us from this pain. My life path finally started to make sense.

In 2018 I stumbled across a remarkable, neuroscience-based therapy called Havening Techniques®. On the first day of my training course, I volunteered to be a subject for a class demonstration, choosing the trauma of my day of abandonment at boarding school. In fifteen minutes the trauma was completely erased. The next time I had a little upset with Meredith, I remained calm, I was able to speak and even express my feelings. We made up and hugged in five minutes. It was a remarkable change. I subsequently erased and healed my other childhood traumas, including the sexual abuse.

Few men come to therapy. Of the clients in my trauma clinic, only 10% are men. Men are left to suffer in silence, ignorant of the traumatic causes of their emotional difficulties. The expression of feelings is often judged to be a weakness, especially in the heroic professions such as the military, emergency first responders, doctors and senior leaders. Many of our business leaders and politicians are deeply wounded men who unknowingly do much harm to the world. Until we start to show them empathy and compassion and develop more authentic and loving ways of being a man, little will change in the world.

If you are curious to learn more about my journey of trauma and healing, read my memoir, ‘The Science of Healing’ available at robinyoungson.com and leading online retailers.