Community Action: How You Can Help

Equality, inequality, privilege and disadvantage are words which are routinely thrust into the consciousness of anyone who is not residing under a proverbial rock in the modern Western world.

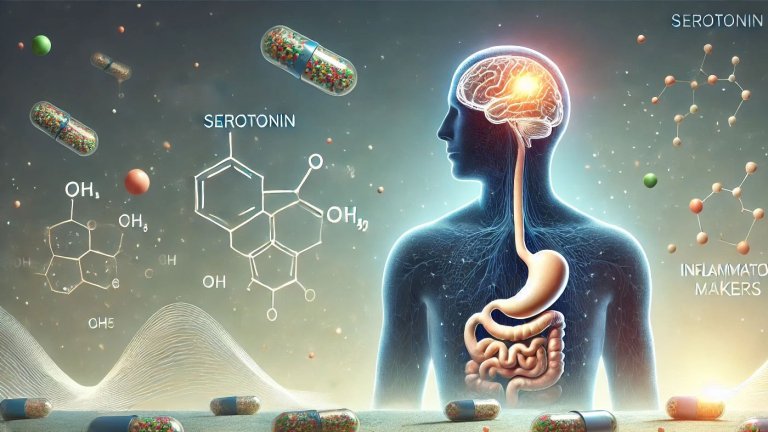

These words convey concepts which are sometimes applied dichotomously and used to sort people into categories based upon characteristics they cannot control, such as race, gender and sexual orientation. This kind of thinking, though not completely without truth or utility, throws nuance to the lions by assuming that a person can be understood as privileged or disadvantaged based upon an analysis of those characteristics alone. While it is true that some demographics are disadvantaged or even maligned more than others, it doesn’t appear to be true that an individual’s privilege or disadvantage can be assessed based solely on such information. Instead, it seems that one of the greatest determinants of individual privilege or disadvantage is one’s mental health (meaning the presence of absence of a debilitating mental disorder). This can be observed by exploring the relationship between mental disorder and poverty, each of which contribute to the other.

Mental disorder and poverty are strongly entwined. Although not everyone who lives with a mental disorder is struggling financially, and vice versa, the two perpetuate one another. An individual who is struggling to cope with the demands of daily life (demands which can be pushed to their limit by the presence of a mental disorder) is likely to lack the energy, enthusiasm and optimism necessary to pursue formal education or a rewarding career; the overwhelming majority of their mental resources are already being consumed by their fight for emotional survival. Many people in this position, in fact, struggle to work at all. Conversely, someone with limited financial resources who lives with, or who becomes afflicted with, a mental disorder may struggle to find the proper care, being unable to afford to access private care and facing the usual obstacles when approaching the public system. In this way intergenerational poverty and intergenerational mental disorder (mental disorder can be transferred both behaviourally and genetically, both of which can transmit from one generation to the next) are two halves of the same self-perpetuating cycle. The public mental health system is woefully overburdened and there are waiting lists and a degree of chance involved; there is no guarantee that the professional you are paired with will be compatible with you. One of the greatest predictors of therapeutic success is, after all, the quality of the relationship between therapist and client.

Noting this, what else, then, can be done to address poverty, mental disorder and the way the two perpetuate each other? On a broader social level this issue can be addressed by individuals, like you, dedicating some time and energy to either working voluntarily for a mental health oriented organisation or, better still, creating and maintaining your own mental health oriented service. Many sufferers of mental disorders are understandably wary (and weary) of large organisations, especially government organisations. They can appear to be impersonal monsters; faceless, apathetic and money-oriented. What people are starving for these days is real human connection, especially in this age of social media and social isolation. For some of these people a person who is working on behalf of an organisation can take on the energy of that organisation and cease to be (in their perception) a truly autonomous human being that they can connect with. Instead, they may see these people as representatives of a “thing”, an impersonal force, a corporate enterprise. Although this perception isn’t necessarily accurate, it is understandable (particularly to anyone who has themselves been seriously mentally disordered).

Perhaps the best way of addressing this part of the problem is for individuals who have overcome, are overcoming or have learned to thrive despite their mental disorder to use their experiences in the service of their community. Sharing your own story can be a powerful motivator and beacon of hope for others. Your success story can benefit others in and of itself, or it can be attached to a community service which you have the knowledge and experience to provide (and living with a mental disorder can provide you with the kind of knowledge and experience which nothing else can). Perhaps you are a persuasive speaker; consider public speaking to raise awareness about your mental disorder and what worked for you in rising above it. Perhaps you are a personal trainer; consider offering a free mental health oriented exercise program (and using your own personal story, or that of someone close to you, to motivate people to participate). Perhaps you are an artist; consider offering a mental health oriented arts class, where people are encouraging to express themselves openly and access the deeper cathartic parts of themselves. Perhaps you are a competent and open-hearted writer, and you wish to share your story with others via this online magazine. Perhaps there was or is something in particular which worked or works for you which you want to share with the world; if socialising and walking in the sun have helped you cope then consider starting a mental health oriented walking group where like-minded people engage in some light exercise while connecting with one another. The latter is the route I chose, but the list of possibilities is endless.

What are your personal strengths? What are your most notable experiences, regarding your experience, be it direct or indirect, with mental disorder? What worked for you and what didn’t? Can you use the answers to either or both of those questions to develop and provide a valuable service to your community?

What many people who are suffering crave for is not simply the support of an organisation, but the guidance of a personality who they can trust and connect with; someone who has been where they are, someone who is driven by a genuine concern for others and the greater good. It would be especially useful to provide a service like this, ideally a free service, to vulnerable communities in particular (communities which are more vulnerable to mental disorder and poverty or otherwise less able to access care). The entwinement between mental disorder and poverty is tight and binding, but we can loosen and even break it, bit by bit, by empowering one another and creating projects which promote mental wellness through exercising regularly, eating well, connecting with others, being creative and changing our negative thinking patterns.

One of the best things about volunteering your time and effort to help your community is that doing so offers you purpose and meaning and helps to further heal any wounds which remain from your own suffering. As well as human connection, it seems that there is a crisis of meaning and purpose in modern society. People feel like insignificant ants whose existences mean little if anything to the world. Whilst this isn’t true, because we all have intrinsic value and potential (and our actions no matter how small, can have an unbelievably large impact on others), often it is by striving toward something and acting positively upon the world that we truly prove our intrinsic value to ourselves! There are two major ways to change negative or dysfunctional emotional responses; by directly changing the thought processes causing them or by challenging those thought processes by engaging in behaviours which conflict with them. If you feel like you lack worth, then strive to create, or get involved with, something worthwhile. Instead of arguing with that voice in your head, prove it wrong!

There is a caveat, however, which must be considered when going down this path, and that is the possibility of disappointment. Motivating people who are suffering is a difficult task. An inherent aspect of mental suffering is, after all, a lack of motivation. Accordingly, your altruistic visions may take some time to properly manifest. When I started a mental health oriented walking group in my home city it took a long time for it to gain momentum. I spent well over a year walking either on my own or with “only” one other participant before the group accumulated enough of a following for us to have regular participants. However, “only” was the wrong way of looking at it. Every little step forward was a success, including the days where “only” one person showed up. I delivered flyers, advertised online and did everything else I could think of to reach the right audience, including speaking publicly about mental disorder and the walking group I was putting together. Sometimes these endeavours worked, other times they seemed fruitless, but every wrong turn was a step closer to finding the right path. There is no real failure, here; only the inevitable growing pains which come with developing a new project.

The mental health system here in New Zealand, especially some of the government funded mental health support organisations which have emerged from the soil in recent years, has helped and will continue to help many people. However, like privately practicing professionals, there are some difficulties in accessing these services; hoops to jump through and lines to wait in. Similarly, our current system prioritises those who are already in immense pain but does little to attend to those who are currently sliding toward that fuming pit of confusion and sadness. The broader public system is, in other words, the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff, and society, especially poorer communities, desperately need people who are willing to guard the clifftops, to usher people away from the edge and toward the sun-kissed gardens of hope, human connection and personal empowerment.